Shader is a game I’m making and stranding on one laptop. Stephen Totilo wrote a great article on his brush with Shader, he relates his personal experience with it as well as my own in making it. It’s a great article because he doesn’t spend time talking about what Shader might mean or should mean. He focuses on what it means to him.

The comments are also pretty great. There are many many people on this article and others calling Shader pretentious and not-novel and dumb and for one reason or another think Shader is bad. And the haters might have a point. There is an argument that commenters haven’t hit on but that I think is important. An argument that Shader could be helping to destroy things I love, that is: the power of clued-in-art to destroy approachable-art.

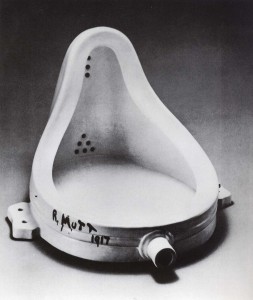

Lets talk for a minute about everyone’s favorite piece of Dadaism: Duchamp’s Fountain. Fountain is pretty hated, then and now, and I think that makes sense. Say you pay a little money to wander into an art gallery in 1917, you’re used to seeing representational art like this but instead are presented with Fountain, or this or, god help you, this. Of course you don’t get it, Fountain in 1917 is exciting to thousands of people, epic representational works are exciting to millions. Unfortunately for you, early 20th century casual art fan, you ain’t seen nothin‘ yet. Modern art pretty much kills representational art.

You’re not really supposed to get Fountain. Duchamp isn’t talking to you, he’s talking to the art world. He’s saying “dude, what does the word art even meannnnnn?” but you’re not super interested in that question. You don’t spend every waking moment of your life thinking about sculpture and painting like Duchamp does. You want something that moves you, something that hits you in the face and makes you say “wow”. You want art that speaks to you. Unforunately for Fountain to speak to you you have to know what’s going on in the art world in 1917. You have to read about and care about art to appreciate it and that’s not something representational art requires. Fountain is just too damned inside baseball for you. But this new kind of art, art that requires a deep understanding of the art world, kind of takes over. It shoulders representational art off the main stage and takes over. You hated Fountain and railed against it, but you lost, and now art sucks for you.

Now you walk into the NY MOMA and are just like “wtf“.

Of course there is great contemporary art that you don’t need an education to appreciate, I wrote a whole blog post about that. Unfortunately a lot of modern art does require deep engagement with the art world and in my oppinion the NY MOMA does a particularly bad job of stuffing itself with unaproachable art. In a way, those of us without an art education lost art. It was stolen from us by the likes of Duchamp and Jackson Pollock.

And so Shader comes to exist. A game (possibly) exciting to thousands instead of millions. Shader is exciting to me because of how it is different from writing a game that might be released. If you don’t write videogames for a living those reasons will not resonate with you. Stephen Totilo plays a lot of games and he plays a lot of games as his profession, but he has a different relationship with Shader than alllll those games he plays so it’s interesting to him. If games aren’t a big part of your life then Shader is probably not going to be interesting to you (i’m not saying that the obverse is necesarily true though).

Shader is too inside-baseball for most people to like, which is not a reason to hate it, but it also might be a tiny shot at populist games. It might be one little piece of kindling on the fire of games that are only interesting to those with a deep understanding of games. And could that fire eventually burn so furiously that it snuffs out beautiful games that everyone can love like World of Goo and Super Meat Boy?