I am very interested in Improvisation in games. One of my favorite things in games is knowing its systems inside out and then being able to play with them in unique ways. To be presented with novel problems I have never solved before and using the tools the game gives me to overcome them, preferably under time pressure.

I am very interested in Improvisation in games. One of my favorite things in games is knowing its systems inside out and then being able to play with them in unique ways. To be presented with novel problems I have never solved before and using the tools the game gives me to overcome them, preferably under time pressure.

It’s no surprise that a lot of my favorite games strongly rely on improvisation; being able to quickly digest new situations and devise a novel solution to it. A list of my favorite improvisation-forward games might include Starcraft, Spelunky and Panel de Pon. These are games I love deeply. Games I have dropped hour upon hour into and never felt guilty about. Games that I am proud to be good at and still have room to grow.

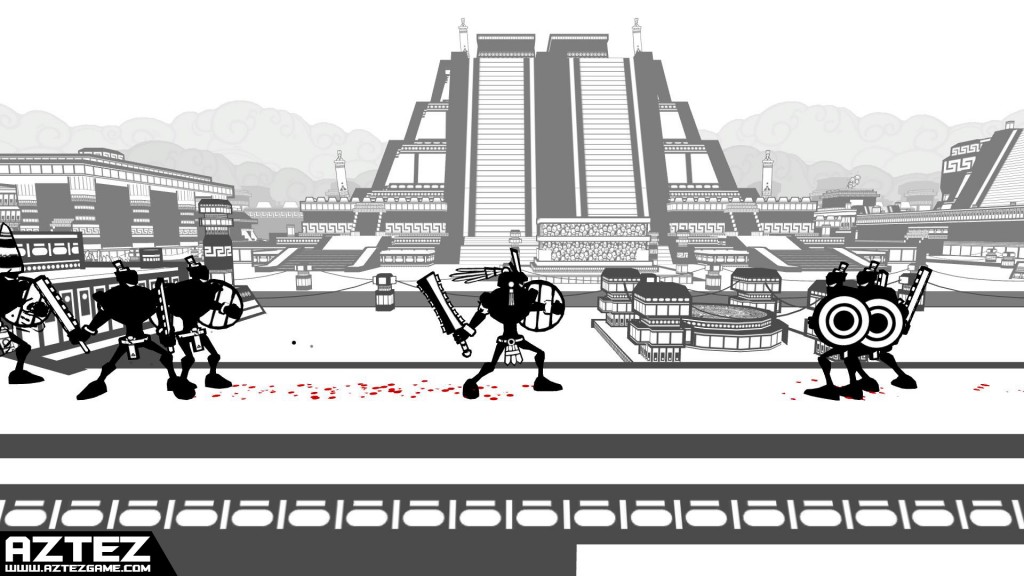

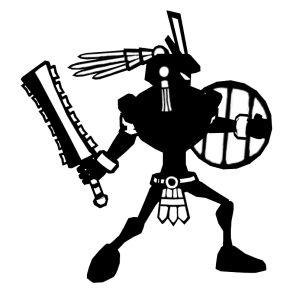

But today I want to talk about Improvisation specifically in the light of Ben Ruiz and Matthew Wegner’s upcomming brawler Aztez. Aztez is still a ways away from release but Ben and Matthew stayed with us for a few months in Mexico so I have had the joy of playing early versions. Before Aztez I had never really played brawlers before (I don’t count River City Ransom, fun but shallow) and dropping into Aztez has been like discovering a new unspoiled continent for me. It’s very good at improvisation and I want to discuss why.

Broad Tools

First Aztez offers you a lot of inputs, a lot of tools. I’m not going to enumerate every move in Aztez but in terms of variables to work with it has: damage, reach, knock-back, knock-to-ground, knock-to-air, stun, grab, parry, lead-up-time, cool-down-time, combos, foward movement, move to air, move to ground, etc… etc… Ben takes these variables and crafts moves out of them which in turn make up your complete tool set. These tools are varied and balanced, they each play a different role in solving the problems the game will present you with.

Combinatoric Problems

This is the beating heart of an improvisation game. What use are tools without problems to solve? Games that use randomness or unpredictable complexity are great at giving players a vast set of unique-but-simmilar puzzles. Aztez has different types of enemies but lets take a case where you are fighting four guys of the same type. Now how many problems do these enemies present you? Very many. The case of on being to your right and three to your left is different from all on the left, the enemies may or may not be attacking, they have different spacing, they have different amounts of health, they may be stunned, they may be on the ground, they may be in the air. The number and state of the four guys defines your current puzzle. Now you decide which tools to use.

This is the beating heart of an improvisation game. What use are tools without problems to solve? Games that use randomness or unpredictable complexity are great at giving players a vast set of unique-but-simmilar puzzles. Aztez has different types of enemies but lets take a case where you are fighting four guys of the same type. Now how many problems do these enemies present you? Very many. The case of on being to your right and three to your left is different from all on the left, the enemies may or may not be attacking, they have different spacing, they have different amounts of health, they may be stunned, they may be on the ground, they may be in the air. The number and state of the four guys defines your current puzzle. Now you decide which tools to use.

I call these problems combinatoric because they are a combination of many simple states. Each single state is easy to understand and the correct response to it is known. But it is their ability to be combined that is their strength. Not only does this generate many new problems for the player but, and this is important, they are all simmilar states. On the face of it this might seem like a disadvantage. You might think you want as much breadth as possible but if you were generating very different states then players wouldn’t get to use the things they have already learned. You want to present them constantly with puzzles that are simmilar to problems they have solved before, so that they have some idea of how to solve them, but problems that are still different, so that they are forced to improvise a slightly new solution.

Many Possible Answers

Think of improvising in music, there is no correct jazz solo, although some solos are better than others. This is part of the joy of improvisation games. By allowing a large number of possible solutions you maximise the player’s chance of finding one. Obviously this has to be balanced with challenge. In Aztez there are always many actions that solve the puzzle but there are many more actions that lead to death. This also leaves room for style. Different players will tend towards different types of solutions. In Aztez you might focus on controling the enemies or on being hard to hit or just brute-force dealing brutal amounts of damage. Players will naturaly develop different skills depending on what tactics work for them early on.

Think of improvising in music, there is no correct jazz solo, although some solos are better than others. This is part of the joy of improvisation games. By allowing a large number of possible solutions you maximise the player’s chance of finding one. Obviously this has to be balanced with challenge. In Aztez there are always many actions that solve the puzzle but there are many more actions that lead to death. This also leaves room for style. Different players will tend towards different types of solutions. In Aztez you might focus on controling the enemies or on being hard to hit or just brute-force dealing brutal amounts of damage. Players will naturaly develop different skills depending on what tactics work for them early on.

Time Pressure

You could have all of the above without time pressure, but time pressure adds a beautiful flow to the game. Without time pressure there is a temptation to spend forever maximising your solution, to sit and stare and calculate. With time pressure you are forced to focus on the bigger picture and to rely on trial and error to figure out the details. This is more fun, why? Who knows, that’s the way the human brain is built. Time pressure frees your frontal cortex from the minutea.

Incredipede, Fantastic Contraption, and the game I’m working on now don’t really use these principles, many great games don’t. But I want to start making games that embrace improvisation. Games that allow players to be artful. I’m even learning to play the flute so I can have a better understanding of improvisation. I hope in the future to make games that let you be a virtuoso every bit as much as Aztez does.