I’ve mentioned before that I am a massive SpaceChem fan. Whenever I’m playing a great game I can’t help but wonder about the process that brought it about so I decided to contact Zach Barth, the designer of SpaceChem, and ask him a few questions. During the interview he was also nice enough to pass along some very early design sketches which I’ve included in the article.

I’ve mentioned before that I am a massive SpaceChem fan. Whenever I’m playing a great game I can’t help but wonder about the process that brought it about so I decided to contact Zach Barth, the designer of SpaceChem, and ask him a few questions. During the interview he was also nice enough to pass along some very early design sketches which I’ve included in the article.

Colin: How did you start working on SpaceChem?

Zach: I started working on SpaceChem in November of 2009 with a friend who, being familiar with my previous works, wanted to make a game. Over the next year we picked up another programmer, a musician, an artist, a writer, and a sound designer. My goal for the project was to up the scope an order of magnitude from my previous games. There were plenty of times when it felt impossible, but with the help of my team we nailed it in the end.

Playing through those previous games you can see ideas evolve from game to game. The Codex of Alchemical Engineering obviously had a strong influence on SpaceChem. When you started SpaceChem what did you want to keep from The Codex and what did you want to change?

Playing through those previous games you can see ideas evolve from game to game. The Codex of Alchemical Engineering obviously had a strong influence on SpaceChem. When you started SpaceChem what did you want to keep from The Codex and what did you want to change?

While I wanted to keep the mechanic of building structures out of “atoms” by “bonding” them together, I also wanted to add a bunch of new ideas that came to me after releasing The Codex, such as inputs being more complicated than a single “atom” and a greater context for the puzzles. I also made sure to fix some of the glaring gameplay errors, such as requiring structures to be built exactly as shown and having the complexity of solutions ramp up exponentially.

Are there other games in the back-catalogue that had a big impact on SpaceChem?

Are there other games in the back-catalogue that had a big impact on SpaceChem?

The defense missions are very similar to the battles in The Bureau of Steam Engineering, as they both require players to build a mechanism to power massive weapons with timing and sequencing requirements.

I found that idea interesting because of its contents and because of my familiarity with it. This is a bit of trend with all of my mechanics: I invent a new problem in the form of a new game and use both brand new ideas and lessons learned from previous games to solve it.

A lot of indipendent game authors take a very iterative aproach to design. Do you work in the same way or do you plan things out from the beginning?

A lot of indipendent game authors take a very iterative aproach to design. Do you work in the same way or do you plan things out from the beginning?

A mixture, really. I started designing SpaceChem by drawing up initial concepts for mechanics, progression, interface, story, and almost every other aspect. After that we wrote a prototype to test out the reactor mechanics and then began working on the full game.

Over the development cycle, though, we changed many details as we learned what worked and what didn’t. For example, pipelines were originally based around an economic model that rewarded efficiency and allowed you to either “pass” or “master” the level depending on how many constraints you were able to optimize for. You could place as many reactors as you wanted and discard as many molecules as you needed to, but in order to “master” the level you’d have to balance the number of reactors against the number of products you chose to produce and maybe not throw away any molecules.

Although I’m sure some of our hardcore fans will think we were stupid for throwing this system away, early playtesting indicated this was far too confusing. After a bit of discussion we vastly simplified the system to a single binary goal of “produce all compounds using the number of reactors allowed and generating waste only if the level includes a recycler”.

How much impact did the rest of the team have on the design of SpaceChem?

How much impact did the rest of the team have on the design of SpaceChem?

Although I was essentially the “gatekeeper” of design, many of the decisions were made as a group, to the point that I can’t even identify who was responsible for what ideas.

How long did you spend on the initial design phase when you were drawing things up?

The initial design phase consisted of a year of spare moments and snippets of conversations that birthed ideas that would go on to make SpaceChem and about two weeks of sketching and discussion when we decided to get down to it. I sketched out most of the design not related to the core mechanics while prototyping was being done by Collin, the aforementioned initial programmer friend.

In prototyping we found that the core ideas could work, but not much more, as the prototype only encompassed the core reactor mechanics and lacked critical touches such as the line drawing and reconfigurable bonders (they were originally all 2×2). As mentioned earlier, a lot of the little decisions about how to make everything fit together nicely were made incrementally.

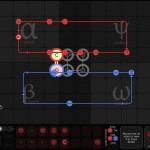

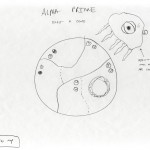

When it comes time to do design, my primary tool is sketching, which forces me to fill in the gaps in ideas that exist only in my imagination and allows me to visually inspect the finished product and imagine how it will function. In the early design sketches you’ll see the cut features I mentioned earlier: pass/master goals, an economic model, and tower-defense style defense missions.

Now that it’s out the internet is peppered with glowing reviews for SpaceChem. I’m a huge fan of the game myself and I’m proud to say I’ve finished every level. The final level alone took me 10 hours to solve though. Were you not worried that the game requires too much stamina and prolonged intense focus? Is SpaceChem written for a specific audience?

Now that it’s out the internet is peppered with glowing reviews for SpaceChem. I’m a huge fan of the game myself and I’m proud to say I’ve finished every level. The final level alone took me 10 hours to solve though. Were you not worried that the game requires too much stamina and prolonged intense focus? Is SpaceChem written for a specific audience?

This was definitely a question that was on my mind, but more truthfully it was something we had very little information about. Some of my previous games were similar to SpaceChem, but were both free and short; we had no idea how players would respond to a scaled up version, let alone what would be the best way to broaden the scope.

SpaceChem wasn’t written with any specific audience in mind, and from what I can tell it hasn’t resonated with any one audience in particular. I’ve read an astonishing number of players remark that they normally don’t like puzzle games, but that they can’t stop playing SpaceChem!

Most important question for last: when are you finally going to write Ruckingenur III?

Most important question for last: when are you finally going to write Ruckingenur III?

Hah! Ruckingenur II is by far one of my favorite projects – it’s just so sexy! The puzzles were really difficult to make and had zero replay value, though, which in addition to the inherent niche-appeal makes me think that a sequel isn’t likely. I hope to explore the general concept more in the future, though…

Thanks very much to Zach for answering some questions about how he and his team designed a great game. You can buy SpaceChem on SpaceChemTheGame.com or on Steam and you can play Zach’s back catalogue of games (including the really excelent Ruckingenur II) at ZachtronicsIndustries.com.

Comments

One response to “Talkin ’bout SpaceChem”

Necro comment.

Cool inverview. I am about to start in on the final level of spacechem. Won’t be surprised if I take even longer than your 10 hours.

I’ve avoided spoilers. videos. etc, but I’ve heard it can be done “cheaty” by just blasting away on not setting up the ability to maneuver. But I’d really feel like I half assed it if I didn’t make something that could dodge as well as shoot. I still feel a little dirty about the level on the previous world where you sort 3 molecules without a sensor (I just stashed the big molecule in the self looping pipe). But that seemed intentional at least, and given my dead center spot in the histograms, maybe it was the most common method.

Again, thanks for the interview, and for your game FC as well. I do love puzzles. And there is something much more satisfying about open ended ones like FC and spacechem, where you’re not just chasing the trail of breadcrumbs increpare left to the unique solution.