It occured to me that some people might be curious about what life as a traveling game author is like. I decided a good way to give you a look into our every-day life would be to write up a day-in-the-life. Here, presented for your edification, is yesterday:

It occured to me that some people might be curious about what life as a traveling game author is like. I decided a good way to give you a look into our every-day life would be to write up a day-in-the-life. Here, presented for your edification, is yesterday:

I woke up at about 6:00 am. I don’t know what it is about the tropics but Sarah and I tend to get up with the sun. Our Internet is usually pretty good in the morning so I reached for the laptop and checked the emails and the facebooks. After tooling around online for an hour or so I got up and greeted the day.

As Sarah slept I wandered down to the beach. I couldn’t see another soul on the eight kilometer stretch of sand and as I walked I left the first footprints since last night’s high tide. It was before the heat of the day and I waded across a few low streams as I mulled over game design problems. I had done my first in-person playtest the previous day so I had a lot to think about. I like to walk and move around when I’m thinking and I like to be somewhere interesting when I think about game design. I’m not sure what role conscious thought plays in coming up with novel ideas and solutions but sitting on a log and watching hermit crabs scurry around seems to generate a close to optimal mindstate. As I was watching the hermit crabs I had a great idea. Actually it was a really old idea that had been rattling around in my head since I first started working on the game. Only now, four months later, was it apparent that this idea might be the puzzle-piece I needed to solve my problems. Play testing is a magical thing.

As Sarah slept I wandered down to the beach. I couldn’t see another soul on the eight kilometer stretch of sand and as I walked I left the first footprints since last night’s high tide. It was before the heat of the day and I waded across a few low streams as I mulled over game design problems. I had done my first in-person playtest the previous day so I had a lot to think about. I like to walk and move around when I’m thinking and I like to be somewhere interesting when I think about game design. I’m not sure what role conscious thought plays in coming up with novel ideas and solutions but sitting on a log and watching hermit crabs scurry around seems to generate a close to optimal mindstate. As I was watching the hermit crabs I had a great idea. Actually it was a really old idea that had been rattling around in my head since I first started working on the game. Only now, four months later, was it apparent that this idea might be the puzzle-piece I needed to solve my problems. Play testing is a magical thing.

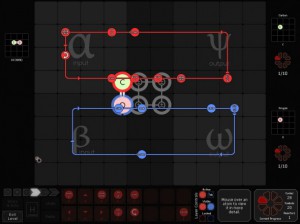

Well when you have a perfect puzzle piece in your head you can’t sit around watching hermit crabs. You have to go slot it into the puzzle! I wandered back over the streams and found Sarah awake and eating breakfast. We talked about some crazy bugs she’s trying to track down in her game Word Dog while I ate some (very unexotic) corn flakes. After I slotted the puzzle piece in I started playing with the new version of the game. It felt really good and I had Sarah give it a play to get a second opinion. It was working really well for her as well and I started to get excited as I imagined other people really liking it. This feeling is like mother’s milk to indie game devs. The thought of players feeling that same soaring joy that you feel playing your game is what keeps you going through the months of doubt and grunt work.

Well when you have a perfect puzzle piece in your head you can’t sit around watching hermit crabs. You have to go slot it into the puzzle! I wandered back over the streams and found Sarah awake and eating breakfast. We talked about some crazy bugs she’s trying to track down in her game Word Dog while I ate some (very unexotic) corn flakes. After I slotted the puzzle piece in I started playing with the new version of the game. It felt really good and I had Sarah give it a play to get a second opinion. It was working really well for her as well and I started to get excited as I imagined other people really liking it. This feeling is like mother’s milk to indie game devs. The thought of players feeling that same soaring joy that you feel playing your game is what keeps you going through the months of doubt and grunt work.

But you can’t do grunt work with an empty stomach and we were in serious need of supplies. We grabbed a backpack, locked up the house, and headed for the beach. We live in Pochote, a tiny fishing village. You can get fish here but not vegetables. To get groceries we have to walk down the eight kilometer beach to Tambor. It’s a long way back and forth in the Costa Rican heat but as far as grocery trips go an 8k walk down a sandy beach butressed by palm trees with scarlet macaws flying over your head isn’t too bad. On the way back we stopped for an hour of body surfing in the larger than average waves.

But you can’t do grunt work with an empty stomach and we were in serious need of supplies. We grabbed a backpack, locked up the house, and headed for the beach. We live in Pochote, a tiny fishing village. You can get fish here but not vegetables. To get groceries we have to walk down the eight kilometer beach to Tambor. It’s a long way back and forth in the Costa Rican heat but as far as grocery trips go an 8k walk down a sandy beach butressed by palm trees with scarlet macaws flying over your head isn’t too bad. On the way back we stopped for an hour of body surfing in the larger than average waves.

We go on a lot of walks no matter where we are in the world and the conversation is usually dominated by talk about games. I really like walking to think about game design. You’re seeing new and interesting things around you and this seems to fire off odd and productive thoughts. Where ideas come from is a grand mystery to me but filling your eyes with exotic sights and talking about what you’re thinking with another game author seems to bring them out of hiding.

We go on a lot of walks no matter where we are in the world and the conversation is usually dominated by talk about games. I really like walking to think about game design. You’re seeing new and interesting things around you and this seems to fire off odd and productive thoughts. Where ideas come from is a grand mystery to me but filling your eyes with exotic sights and talking about what you’re thinking with another game author seems to bring them out of hiding.

When we get back I’m excited enough to grab the laptop and head next-door to do a little more in-person play testing. We live next to a bar and children’s music school run by a family of Canadian Costa-Ricans. That sounds like an odd mix and maybe a mix that you wouldn’t want to live next to without ear protection but that’s really not the case. Harmony Music School and Gabe’s Bar are as wonderfully as the family running them. They’ve made this tiny fishing village one of our favorite places in the world and they’re in competition with places like Tokyo and Istanbul and Edinburgh. The best part of travel is the people and the people here are great.

When we get back I’m excited enough to grab the laptop and head next-door to do a little more in-person play testing. We live next to a bar and children’s music school run by a family of Canadian Costa-Ricans. That sounds like an odd mix and maybe a mix that you wouldn’t want to live next to without ear protection but that’s really not the case. Harmony Music School and Gabe’s Bar are as wonderfully as the family running them. They’ve made this tiny fishing village one of our favorite places in the world and they’re in competition with places like Tokyo and Istanbul and Edinburgh. The best part of travel is the people and the people here are great.

Gabe is about our age and is my local play-tester. If the game was in a more finished state I’d get everyone I could lay my hands on to play it but as it is Gabe’s English-speaking, game-literate, mind is a perfect and rare commodity. I trucked my laptop over to the bar and Gabe sat down to give the new version a play. His reaction was really gratifying. He lamented some of the quirks of the old system disappearing but was immediately sucked into the game more deeply than before. I find it easier to trust players behaviour rather than their words so when he ran out of levels and just started playing around randomly for fun I was a happy person.

Gabe is about our age and is my local play-tester. If the game was in a more finished state I’d get everyone I could lay my hands on to play it but as it is Gabe’s English-speaking, game-literate, mind is a perfect and rare commodity. I trucked my laptop over to the bar and Gabe sat down to give the new version a play. His reaction was really gratifying. He lamented some of the quirks of the old system disappearing but was immediately sucked into the game more deeply than before. I find it easier to trust players behaviour rather than their words so when he ran out of levels and just started playing around randomly for fun I was a happy person.

By this point it was about three o’clock. I probably should have gotten back to the house and done some more work but instead I spent the next several hours playing pool. I have to admit, I don’t work super hard, but this day was pretty lazy even by my standards.

Sarah was beavering away on the deck when I dropped off my laptop and I could not entice her to abandon her work to skive off with me and play pool. Not until the impromptu pot-luck started up did she make it across the yard to Gabe’s. A couple of local musicians had decided to put on a little show last night so people started wandering over to Gabe’s at about 5:00. By happenstance a lot of them had food with them. We ate Jambalaya, fish caught out of the ocean an hour earlier, and, amazingly, freshly made Kimchee! Freshly made Korean Kimchee in Costa Rica! Thank you Kee Bum!

The concert was great and the evening was filled with the student musicians, local fishermen and guides, expats, and all the rest laughing drinking and eating.

The concert was great and the evening was filled with the student musicians, local fishermen and guides, expats, and all the rest laughing drinking and eating.

That’s what being a traveling game author is like. It’s like being a regular game author but much much better.